Stress, Starvation, and Survival

By Dianna Bell

.

Underwater Ghost Towns

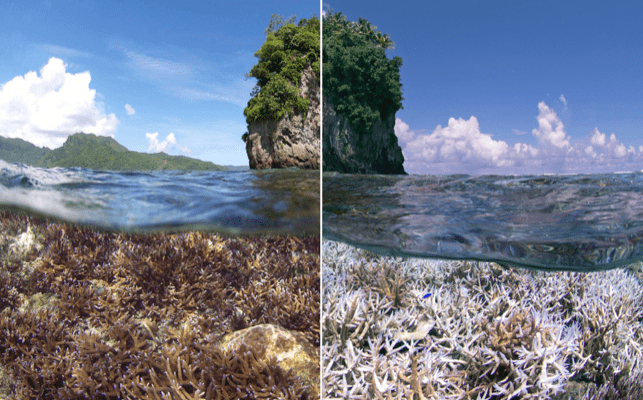

White ghosts rising from the seafloor. Snow-covered skeletons. Faded rainforests under the sea. Once vibrant and thriving coral reefs are suffering, and dying off at alarming rates.

“It’s devastating,” said Dr. Steve Whalan, one of the scientists on the Earthwatch expedition Helping Endangered Corals in the Cayman Islands. “If you’ve ever spent any time on reefs, they’re absolutely fascinating, remarkable systems visually. It’s awe-inspiring to see some of these systems in place when they’re not degraded. So to see them crash around you is very sad.”

The culprit of this destruction? Coral bleaching, a process caused by warming sea temperatures. These rising marine temperatures are caused, in part, by climate change, which is impacting our oceans in several ways.

Earlier this year, Dr. Terry Hughes, Professor of Marine Biology at James Cook University in Queensland, Australia, convened Australia’s National Coral Bleaching Taskforce to assess the state of bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef.

Although he knew that temperatures had been rising, he was unsure of the extent to which the reef had been damaged. As he flew over the 911 coral reefs surveyed, he quickly realized the bleaching was more severe than he realized.

“This has been the saddest research trip of my life,” he said in a statement. “Almost without exception, every reef we flew across showed consistently high levels of bleaching, from the reef slope right up onto the top of the reef. We flew for 4,000 kilometers in the most pristine parts of the Great Barrier Reef and saw only four reefs that had no bleaching.”

The extent of the bleaching, he said, was more severe than he has ever seen.

.

.

.

What is coral bleaching?

As sea temperatures rise, corals become stressed. In order to preserve themselves, they expel the algae (called zooxanthellae) that typically inhabit their polyps – algae that provides the vibrant colors corals are known for as well as the nutrients and oxygen corals need in order to survive. Losing the zooxanthellae and the food source that comes with this symbiotic relationship puts the corals in a fragile and stressed state, leaving them more susceptible to disease, and ultimately death.

.

The most recent data suggests that more than 90 percent of the reef has shown signs of bleaching. And this isn’t an isolated event. Coral bleaching has been seen worldwide in what the U.S. National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has deemed the “longest coral bleaching event” on record, prolonged by global warming and this year’s El Niño, which ushered in warmer temperatures – predicted to last through early 2017.

Coral bleaching is generally a normal process, said Dr. David Bourne, research scientist with the Australian Institute of Marine Science and lead scientist on the Earthwatch expedition Recovery of the Great Barrier Reef. “However, the fear is that the disturbances are becoming more frequent and hence the time periods between recovery are shrinking, thereby contributing to a slow decline in coral cover on reefs.”

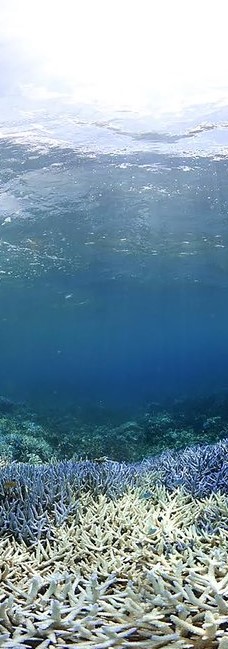

Lagoon of Ermitage, Réunion Island, in the Indian Ocean during the coral bleaching event in April 2016. © Reef Check France

The first global bleaching event occurred in 1998, an El Niño year that brought about record-high sea temperatures. Some countries lost 90 percent of their living reefs.

In the Cayman Islands, oceanographer Dr. Carrie Manfrino (who is now lead scientist on the expedition Helping Endangered Corals in the Cayman Islands) saw the results of the bleaching first hand.

“I was doing some research and noticed that the reef had been impacted quite heavily. I decided that we needed to do more than just look at the mortalities,” she said. “We really needed to try and do something about what was happening with reefs on a global scale.”

With the haunting images of starving corals in her mind, Carrie created the Central Caribbean Marine Institute (CCMI) on Little Cayman, the smallest of three islands in the Cayman Islands, with the goal of protecting the future of coral reefs through research, conservation and education.

.

.

Rainforests of the Sea

Coral reefs cover just 0.2 percent of the world’s seafloor, but they’re home to a quarter of all marine species: reptiles, crustaceans, seaweed, fungi, bacteria, and over 4,000 species of fish. Reefs provide shelter from predators, storms, and ocean swells, and offer spawning and nursery grounds for fish species.

Not only that, approximately 500 million people worldwide depend upon reefs for food. Reefs provide fishing, recreation, and tourism jobs and income to local economies, and protect coastlines from storms and erosion.

“On the Great Barrier Reef alone, there’s a $5 billion-a-year industry associated with the reef,” said Steve. “Add that up around the world and you can understand just how important they are economically, culturally, and—most importantly—ecologically.”

But not enough is being done to protect these vital ecosystems. Most studies are geared toward waiting to see signs of stress on the reefs, but fewer efforts have been made to counter the effects.

“We can monitor until the cows come home in terms of what’s happening when the temperatures start to rise and what we see,” Steve said. “What’s just happened on the Great Barrier Reef is a classic example – everyone was seeing these temperatures rising and staying on a little longer in the year and hoping that things weren’t going to crash down around the corals in terms of bleaching events, but it did.”

Coral bleaching isn’t always a death sentence, however. It’s not too late to turn the tide and protect the global health of coral reefs.

.

.

.

Recovery on the Reef

Even after the bleaching event in 1998, the corals of Little Cayman tell a story of survival. Between 1999 to 2005, 40 percent of the corals off the island died. But then in 2009, the reef began to show signs of improvement and by 2012, the remaining corals had entirely recovered.

Carrie was astounded by this recovery. It was one of the few reefs in the world to recover after the 1998 El Niño year. At a time when some countries had lost 90 percent of their living reefs, Little Cayman was on the road to recovery. But why? What enabled the corals off of Little Cayman to make such a comeback?

Carrie was determined to answer this question and, in 2013, she turned to Earthwatch for support. Rather than adopting a stance of reaction when these events occur, she proposed to study reef resiliency in order to help reefs around the world better prepare for these events and increase the rate of recovery.

To do this, it would require detailed mapping and surveying of Little Cayman’s reefs – areas largely comprised of endangered and threatened coral species.

“We have 10 full-time staff here at the Central Caribbean Marine Institute servicing the operations and leading the education and science programs,” Carrie said. “But even with those numbers, we have probably four individuals who can go out into the field at any one time.” But it wasn’t enough. In order to collect the amount of data needed, it would require many more helping hands than were currently available to the researchers.

In 2015, the first team of Earthwatch citizen scientists took to the waters, snorkeling, surveying the reefs, and mapping corals around the island. They also helped to grow new corals in nurseries – the largely threatened Acropora cervicornis (staghorn coral) and Acropora palmata (elkhorn coral) species.

In just one season of fielding, volunteers out-planted 22 new colonies of the endangered staghorn coral species to an area of a reef in Little Cayman now affectionately called “Earthwatch Rock.” They helped scrub 69 coral skeletons in preparation for coral spawning season– a step in monitoring whether long-dead skeletons can act as new settlements for larvae of this endangered species. Volunteers also helped map the locations of 88 Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) corals around the island, which will help CCMI researchers determine population demographics and reef resiliency.

The efforts of Earthwatch volunteers will help with long-term monitoring, which will help secure a future for corals globally.

And while these are necessary steps, there is more work to be done.

.

.

.

Seeds of Change

Warming ocean temperatures aren’t the only factors causing coral reef mortalities. Human activities such as overfishing, coastal development, agricultural runoff, and pollution are all causing reef destruction, and they can all be prevented.

But where do we begin? Dr. Whalan and Dr. Bourne both suggest starting with yourself.

.

Seeing a major area of one of the most special places on the planet die during our watch has to be a concern for everybody.

— Dr. David Bourne

.

He suggested finding ways to reduce our carbon footprint, reduce waste, and think about the environment around us. “Often we feel disconnected from the problem since it is remote from us, however, what we do locally has an impact globally.”

This global impact is felt heavily in Little Cayman. I recently returned from the Earthwatch expedition there, and one of my most memorable moments came during a beach clean-up.

The five members of my team dispersed on a small section of beach in front of a local restaurant and collected 10 bags of trash, waste that’s coming to the island from all over the world.

Little Cayman is home to 150 to 200 people, depending on the time of year. Yet every day, bags and bags of garbage wash ashore.

Seeing the many discarded items on the beach was a revelation for me. Despite my own eco-friendly nature, I have a carbon footprint, and this has widespread effects – effects I had previously never seen laid before me so clearly.

As I picked up bottle caps, toothbrushes, shoes, contact lens cases, medicine vials, and various forms of plastic, I was reminded of something CCMI’s Education and Outreach Instructor Katie Correia told us on our very first day. We had been gearing up to snorkel, and she bent down and picked up a smooth brown shiny rock-like object. She brought it over to us and informed us that it was a sea bean: the seed of a fruit that drifted out into the ocean, sometimes carried for hundreds of miles. She told us the one in her hand most likely came to the island from Central America.

While collecting trash from the shore, I uncovered some of these sea beans. Just like the waters carried the seeds of tropical trees to new lands, so did it bring the discarded objects of humans from miles and miles away.

Our actions matter. Whether we intend to or not, we are making a difference. During my time in Little Cayman, I was reminded that I have the power to choose whether my actions will help or hurt. We all do.

.

.

Join Us

Coral reefs live in a stressful world. Due to climate change and carbon dioxide emissions, they have to deal with rising sea temperatures and increasingly acidic ocean waters, which make them more susceptible to disease and death. The coral reef off Little Cayman Island tells a story of survival in the face of these challenges.

What makes this coral reef resilient? On this beautiful island, find out how we can help reefs survive climate change.

.

If you have any comments or questions related to this story, please contact us at communications@earthwatch.org. We welcome your feedback.

Sign up for the Earthwatch Newsletter

Be the first to know about new expeditions, stories from the field, and exciting Earthwatch news.